“He not busy being born is busy dying.” Bob Dylan

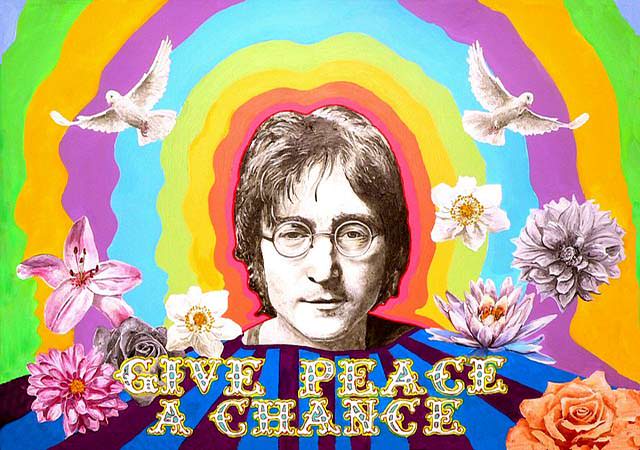

The Baby Boomer generation, those born in the euphoria following World War II, took that phrase to heart. It’s alright, Ma, we’re only bleeding, getting high, moving to the suburbs, going to college, raising families, but never giving up the code of hip, or our beloved rock ‘n’ roll, itself spawned in a time of plenty.

When Baby Boomers turned inward and began navel-gazing, so did singer-songwriters like James Taylor, The Eagles and Jackson Browne – not to mention New Age crystal dealers and yoga instructors. When it was time to embrace parenthood, we went at it with the kind of passion which fueled helicopter over-protection and the awarding of soccer trophies for participation, dreaming of a hippie egalitarian idea we’d already dumped in favor of yuppie consumption.

So, it truly figured, if Baby Boomers romanticized every phase of life that they went through, then mortality would be the logical next step for our all-encompassing self-absorption: the notion of how to die now becomes paramount in an age when concepts like destination funerals and death with dignity are not just abstractions – they are part of our daily lives.

If it weren’t clear – in the immortal words of Jim Morrison — “No one here gets out alive.”

But how we approach that end will make all the difference. Do we want to be cremated or buried? In the earth or at sea? Have a large funeral or just a gathering of family? What exactly do we leave behind? And why were we even here in the first place?

Jim Morrison with The Doors.

Picture Courtesy of Pixabay

Generations come and go, strutting their moment in the spotlight, and then fading. Obit Magazine endeavors to make death come to life, before life succumbs to death. As long as you’re reading this, you’re on the right-side of the great divide – pre-OBIT.

This year has been one of tremendous loss for a generation now with a toe already in its 70s. David Bowie’s surprise demise on January 10 ushered in 2016 with a shock to the system, much as the artist formerly known as Ziggy Stardust, etc., had always done in his music and art. Turning his death into a creative project, his new album, Blackstar, was released literally two days before he passed, introduced via a video for the song, “Lazarus,” which was nothing less than the artist preparing us for his own death, as neat an illusion of life after death as a voice from the great beyond could be.

That Bowie represented the various possibilities of reinvention cloaked in the various guises of popular culture – a lifelong Baby Boomer obsession for sure – not only marked the end of an era, but the uneasy transition into the hereafter for a generation that prided itself on cheating death.

Picture Courtesy of Pixabay

Bowie’s passing was followed by the deaths of Baby Boomer icons like country great Merle Haggard (who correctly predicted he’d pass on April 6, his 79th birthday) and ‘80s superstar Prince, whose sudden demise from an opiate overdose a little over two weeks later on April 21, was just another unwelcome reminder that the Grim Reaper doesn’t visit just those suffering from old age or physical illness.

Obit Magazine will embrace death for all — not just for the kind of beloved public figures you see eulogized in your local newspapers, like Bowie, Haggard, Prince, Gene Wilder or Edward Albee. Even the death of a random butterfly can upset the order of things, but for most people, losing someone close to them will be their most poignant brush with last rites.

My father died from cancer in 1997 in Florida in between two trips I made to visit him, the second for his funeral. Seeing him reduced to a frail, barely conscious state was almost too much for me, but not unexpected given the natural order of things. But when you lose your kid sister at age 61 after a lifetime of bipolar disorders, unhappiness and physical illness, it sets off a whole other meditation along the lines of David Byrne’s “How did we get here?” And the unspoken where do we go next?

My sister Janet went into a mostly comatose state after a bout of pneumonia and didn’t emerge for two weeks. The decision was made by me and my parents to take her off life support at that time, and – with a combination of emphysema, an overdose of lithium and who knows what else – she didn’t last for more than three days when I got the call in the middle of the night she had passed.

My sister never wanted much, but her last wishes were to be cremated and have her ashes scattered in the Pacific Ocean. I dutifully picked up the surprisingly heavy box which held her remains, and tucked onto my book and record shelves, temporarily unable to let go. Inside the brown box was a plastic bag affixed with a metal ring on which was hooked a silver disc with a number on it. 12667. The only way to tell exactly whose ashes I’d been given.

Two weeks passed to a month, then two months and three, and that box remained on my shelf, even as my mother begged for some sort of closure. Finally, one sultry August night, planning to attend a Mavis Staples concert on the Santa Monica Pier, I made my decision. That would be the evening. We walked along the beach, within sight of the Raymond Chandler-esque apartment she once lived in on Appian Way in the ‘80s, alone now among the multimillion dollar condos and the exclusive Shutters Hotel which had been built around it in the ensuing years.

I folded up the cuffs of my jeans and began wading out under the pier, ripping a hole in the bottom of the plastic bag, letting the ashes drift out into the water. The undulating tide had them coagulating around my knees, as I recalled a similar scene in The Big Lebowski, where the Dude and Walter scatter Donny’s ashes, only to have them blow back in their face.

A weight was somehow lifted off my shoulders. With a full moon blazing in the sky, Mavis Staples burst into her signature song, “I’ll Take You There,” urging us into a call-and-response that got downright spooky when I imagined my sister’s spirit inhabiting the gospel queen’s similarly rotund body and short, bobbed hair. It’s about as spiritual as this cultural Jew-Woody Allen atheist is capable of getting.

I’m not afraid of dying. I find the Obit Magazine project a celebration of the inevitable culmination of one’s life.

The feeling of loss resides only within the living, the survivors, which is why death itself has a special poignancy, like the end of a particularly satisfying narrative.

Boruch Alan Bermowitz was a friend of mine. You may – or may not – known him as Alan Vega, lead vocalist of a two-man new/no wave punk-rock group sporting the incendiary name Suicide. I used to work with them in the ‘70s, and despite their grisly moniker, they were artists who used the name to – and here’s that word again – shock its audience out of its complacency into embracing life on their own terms. Their unorthodox approach to music – a clattering keyboard cum drum machine manned by one Martin Rev, with Alan laying out his Elvis-meets-Iggy pop vocals – alienated many, but eventually, like all great avant-garde experiments, resonated with a subsequent generation, which turned them into living legends.

Vega passed away on July 16, just two years after the death of his one-time manager Marty Thau – the same man who discovered the New York Dolls and hired me for one of my first gigs in the music business as the “Minister of Information’ for his punk-rock label Red Star Records. I was just a kid then – newly emerged with a Masters in Film Criticism from Columbia University, and ready to convert the world to my incipient punk-rock revolution. Now, 40 years later, Thau and Vega – two of my role models in cultural appropriation – were gone. I had been meaning to call Vega when Thau passed, and indeed, even as I got news of his passing, I had his phone number on my desk waiting to call and exchange jibes about our beloved New York Mets. Alas, that would never happen, and it made me sad. Lesson learned: if you feel it, do it!

Obit Magazine is not so much about death, but life, and how it’s affected by death. I only wish to stay alive long enough to see it fulfill its mission. This Baby Boomer refuses to go gently into that good night, but instead looks to accept his fate with a degree of equanimity, having accomplished at least part of what he set out to do. Not unlike Leo DiCaprio at the end of The Revenant, staring directly at us through the camera’s lens. Let’s all transcend together.