Prior to making “Obit,” her surprisingly charming and lively documentary on the New York Times obituary pages, Vanessa Gould was not an avid reader of the obituary page.

That’s understandable. The New York-based filmmaker is too young to be scouring the obits. She talks about her film in quick but considered enthusiasm that make apparent how much she’s thought about her subject, and interest that was piqued when Éric Joisel, the subject of her previous documentary, “Between The Folds,” died.

The obituaries desk in The New York Times newsroom.

Picture Courtesy of Obit. Documentary/Kino Lorber.

He died from lung cancer at 53, and she sent a death notice out to a dozen newspapers. Only the Times’ Margalit Fox replied. They were interested. But when it came to time to answer questions about Joisel’s youth, there was much she couldn’t answer.

“Some said he studied law, some said he studied sculpture. Some said he had married maybe at a young age and it didn’t last.” These facts, she realized, “were lost to history.”

And she was left with the sense of a life and work cut short. “It felt like he was going to start slipping through my fingers like sand—his memory and the value of his work. Because there was nothing in place to remember him, and his work was so singular.” She hadn’t anticipated that, and the thought stuck with her. She became a regular reader of the obituary pages.

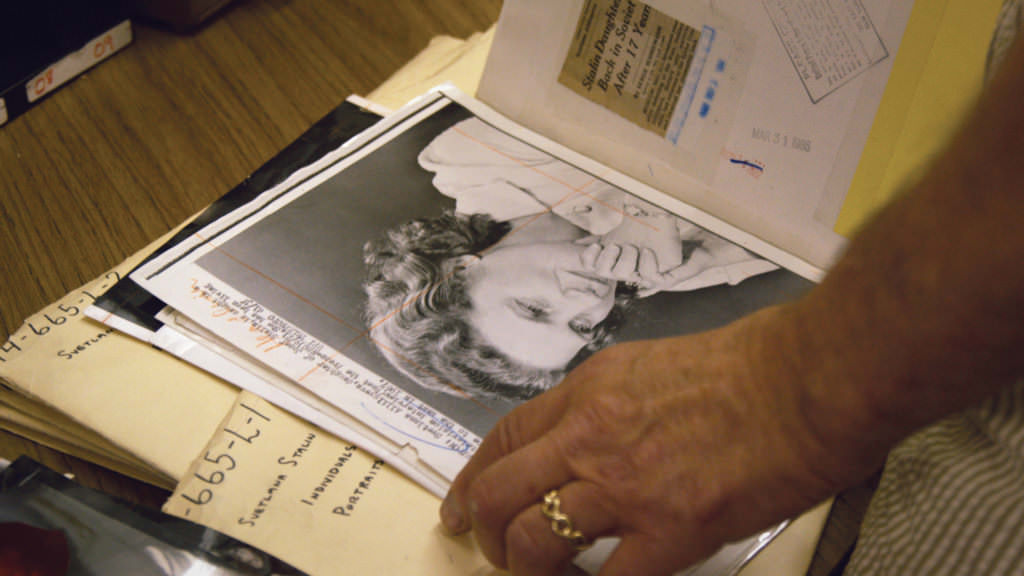

A glimpse into an old folder in The New York Times morgue.

Picture Courtesy of Obit. Documentary/Kino Lorber.

Reading them, she recalls, felt like “catching history before it falls away.” As Fox tells her “Obituaries have nothing to do with death and everything to do with life.” It wasn’t the popes and the presidents who were most compelling, Gould says, it was reading the stories of the people you hadn’t heard of, whose lives were “a riveting thing to read about, and maybe touched your life.”

As a documentary filmmaker, she felt that every single obituary could be a documentary. The solution, she says with a laugh, was to “go meta,” and “make a film about all of them. “

She brought her idea to Fox, who was interested. It took about a year until the Times finally gave its ok. “They weren’t closed to the idea,” she says, “but they were really cautious. They can’t indulge the whims of every filmmaker that walks through the doors” But the Times’ management and the writers “were curious enough to indulge me and, as we got to know each other, we developed trust.”

That trust is repaid in the movie. “Obit” falls into the category of media documentaries, joining “Page One,” “The September Issue,” and “Bill Cunningham New York” in pulling back the curtain on how the news comes together.

Gould followed the paper’s obituary writers (Bruce Weber, Margalit Fox, Paul Vitello, Daniel Slotnik) and editors (William McDonald, Peter Keepnews, Jack Kadden) on a typical day, from deciding who deserves to be included in the paper, assigning stories, the research and finally, getting the copy in before the 6PM deadline.

But it’s Jeff Ross, the last remaining employee in the Times labyrinthine morgue, who almost steals the show. Gould talks about him with great affection, calling him “ the secret weapon of the obit staff.” He’s the man who knows where the bodies are metaphorically buried, even though he admits that if something’s misfiled, it’s lost forever.

Gould speaks with great admiration of the staff. “They have this constellation of qualities that make them good obituary writers: an interest in history, an ability to work under pressure and write on deadline, be a great generalist, talk to people at a difficult time—all these sort of expected things, but they’re also really empathetic people….who are able to connect with and capture our humanity and are able to put on a page.”

She ended up reading all their obituaries, taking notes that filled up notebooks. Getting the chance to do that, she says, was a “great privilege. To have the opportunity to read them all and fall into historical wormholes. “

For all that, “Obit” was a very quick shoot, with principal photography taking up less than 100 hours.

She only had a day or two with each of the editors and writers, sometimes even less. And she lucked out. The day she tailed Weber, he was assigned the obituary for media consultant William Wilson, and the work that went into that story is the narrative spine of the movie. The movie opens with Weber calling his widow, and ends with the discovery of an error in his story.

Obituary writer Bruce Weber.

Picture Courtesy of Obit. Documentary/Kino Lorber.

Wilson’s main claim to fame was advising John F. Kennedy on how to campaign on television, including applying JFK’s make-up and insisting on a specific podium for the first Kennedy/Nixon debate, an event that even Kennedy admitted sealed his election.

As the day went on, Gould realized how lucky she was. “It was really good. The story had the Kennedy aspect, and it had the meta-media element,” and by the end of the day, she knew she had her story, and told Weber they wouldn’t have to film the next day.

But “Obit” is not about a single obituary. It is about the changing attitudes of both obituary writers and readers, moving from being the grayest part of the Old Gray Lady to vital and vibrant mini-biographies. It delights in uncovering some of the more memorable (and oddest) people who have rated New York Times obituaries. There’s wonderful footage of, among others, John Fairfax, who rowed, solo, across two oceans; Thomas Ferebee, the bombardier of the Enola Gay; and Marshall Lytle, bass player of Bill Haley and the Comets.

Gould describes finding the archival footage as ”a whole other project” that took more than a year to complete. But she had no doubt of it’s necessity. Writing is not an especially visual pass-time; there’s only so long that people will watch someone sitting at their computer. But she say it as “a way to re-animate these people. Or resurrect them from the dustbin of history.”

Besides, she says, “what other excuse will you find to dig up virtually anything and put it in a film?”

Many of the movie’s best clips were acquired from small archives off the beaten track. “We really were going from the unknown stuff, the weird stuff, and we cast a wide net, and saw what our archivist came up with.”

Her tenacity paid off handsomely in the case of Wilson, a truly behind-the-scenes guy. So much so, the paper couldn’t even find a picture of him. “We didn’t think we were going to get anything of him, he would have to exist in our imaginations.”

But somebody found a film canister that contained footage shot during the hours before the debate. “We couldn’t believe it,” she says, still sounding enthusiastic, years after the fact, “that’s our guy!” The crew kept watching, and they heard him laugh, and the editing room cheered. “We felt, she says, “that we had communed with him in some way.”

By the end of “Obit,” you might feel the same way about the Times’ obituary staff.

“Obit” opens today in Los Angeles, while continuing in New York.

Leave a Reply